Physics Professor Mary Holden Contributes to Research with the Federal Bureau of Investigation

Fractures tell stories—and according to Mary Holden, assistant instructor of teaching of physics, the study of glass fractures has been helping forensic scientists at the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) when investigating cases that involve various types of human bone breakages.

Recently Holden worked with the FBI to curate a manual entitled A Guide to Forensic Fractography of Bone that was published by the US Department of Justice. In addition to offering her specialized knowledge, Holden also contributed photographs for the purpose of familiarizing readers with the science of fractography and acquainting them with the visual knowledge necessary to effectively apply the field of study to human bone.

“Markings on broken material tell a whole story of its past. There is always a puzzle to be solved," explains Holden. “You’re taking a transient event, a fracture, and now looking at the pieces and going backwards to decipher how it occurred. If a material breaks I can piece it back together, explaining what happened and why it happened. I can also calculate what stress the material broke at. This skill took time to develop which I learned by breaking samples and examining them."

Fractography is the science of examining fractured materials, commonly used to identify structural failures or determine outside causes for a material’s rupture. It is a practice applied to numerous fields outside forensics including engineering, physics, anatomy, art, and even legal contexts—where fractography specialists are requested as expert witnesses to testify in glass production lawsuits for cookware, wine bottling, and medical field appliances.

“While much of the data presented in expert legal testimony can be subjective, fractography offers objective, evidence-based insights,” says Holden. “It is a science based on fracture markings that prove what happened.”

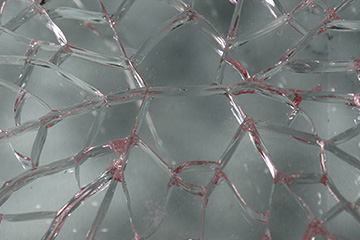

Photograph of a broken panel of glass Holden provided for the FBI

Photograph of a broken panel of glass Holden provided for the FBI

The images Holden provided for A Guide to Forensic Fractography of Bone included bottles with pressure breaks and glass panes broken by tension and impact. Due to glass’ clarity, fractures are clearly seen, allowing readers of the manual to readily learn the propagation of different types of breakages. Holden broke the glass samples herself to ensure that the breaks accurately displayed the variations of fracture characteristics.

Extending her fractography research to human bone, Holden frequently visited her local butcher to collect samples of pig bones, which have structural similarities to human flat bone. The FBI suggested that Holden begin her research with flat bone, which involved studying the skull, the sternum, and the scapula. Although denser in composition compared to human bone, pig bones have provided Holden with the necessary material to collect data on how bone responds to impact and pressure-induced fractures.

“The fracture of bone is new to the world of fractography,” says Holden. “Scientists at the FBI requested that I include this information along with my glass studies.”

Holden serves as the only university-level instructor specializing in fractography of both glass and skeletal bone. This distinction provides valuable educational experiences for her Seaver College undergraduate students. Annually Holden invites students from various disciplines to participate in her research initiatives where they work alongside the director of the FBI’s forensic lab division.

Holden and her student researchers present annually

Holden and her student researchers present annually

This spring at the Southern California Conference for Undergraduate Research (SCCUR) Holden’s student researchers will be presenting their findings on the fracture characteristics of tibia and femur bones by using glass models. By filling glass tubes of comparable size with a fluid of similar viscosity to bone marrow, students investigated impact and pressure breaks by calculating the force that initiated each crack.

Composed of both undergraduate and graduate students, Holden’s research cohort involves individuals from diverse academic programs, including biology and chemistry majors, graduate psychology students, future dental studies students, and a 3/2 engineering major who plans to pursue biomedical engineering. Additionally Holden extends her educational opportunities to students interested in pursuing orthopedic surgery who will provide care for patients with compromised bones.

“Many of these students love these research projects because they are so hands-on, and the findings of each investigation are applicable to different fields,” says Holden. “The challenge of solving these puzzles applies to not only forensic specialists, but to anyone interested in the story of what happened to broken material and identifying the source of stress that started the crack.”

Holden will be contributing to another forthcoming fractography publication for the Forensic Department in Quantico, Virginia FBI lab, while continuing to solidify her position as an expert within the vast field of fractography.

“It takes patience and artistry to observe fracture markings while knowing how to maneuver lighting to notice the nuances and the story every fracture tells,” says Holden. “It has been a rewarding experience to contribute to the FBI’s printed material, and I hope to continue inspiring my students with this specialized knowledge.”