Seaver College Professor John Taden Researches Impact of Social Media on Democracy

More than 5 billion people in the world today are social media users. This means that 63 percent of the global population is digitally conjoined by connective apps and websites. In 2027 these numbers are expected to balloon toward 5.85 billion and 70 percent. The full weight of this digital revolution is still unknown; however, the societal shifts it could spur are in the process of being analyzed.

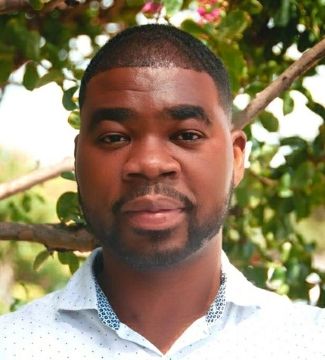

John Taden, an associate professor of international studies at Seaver College, with coauthor Alex Acheamphony from Bond University in Australia, recently published research investigating how social media affects democracies around the globe. The two professors gathered data from 145 democratic nations to determine whether social media is a depressant, harming the merits of democracy, or a stimulant, enhancing the positive qualities of elected governments.

“Social media provides us with snippets of news that are largely stripped of context,” says Taden. “One of the reasons we conducted this study was to determine how social media usage affects various democratic institutions and to test the role of the internet itself in the process. For individuals, does internet access accelerate the process of finding the full story and learning something?”

Taden and his colleague show that while social media generally enhances all types of democracy, the broader use and accessibility of the internet affects which countries benefit from and which countries are harmed by social media usage.

Overall, they discovered that people from high-income nations, or nations with ubiquitous internet access, benefit from social media, as the public participates in the democratic process at a higher rate and citizens have greater access to their representatives.

In contrast, democratic nations where incomes are low and internet access is limited are harmed by social media. The rich, political elites in these countries wield an internet access advantage over the average person, which allows them to influence political narratives in ways that are always intended to strengthen their grip on power.

This access deficit also deteriorates the public’s ability to connect with representatives, hold representatives accountable, and stay in the know concerning ongoing issues, or participate fully in the democratic process.

“Social media helps citizens hold their leaders accountable,” says Taden. “It rapidly grows public knowledge by updating everyone in real time. This immediate way to broadcast information enhances citizens’ ability to connect with their elected representatives. In high income countries, with the added advantage of a high speed internet connection, citizens are able to verify information more easily and are also able to organize more quickly to hold leaders accountable. However, if you are in a country where internet coverage is limited and slow, you don't have that real time advantage.”

Ease of social media access and fast internet speeds do not guarantee an informed populace, but they do help jump-start one. In order to wield this connective combination effectively, Taden explained that the constituents must remain active learners as opposed to static consumers. Rather than believing the claims and accounts found on social media outright, individuals must be willing to mine for further context from trusted and reliable news sources.

Taden and Acheampong’s research represents a large-scale effort to study the effects of social media. To compare and contrast 145 nations, the two professors had to account for the many minute, dynamic differences that each individual democracy boasts. They accomplished this feat by relying on a distinctive dataset called Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem). V-dem classifies democracies around the world using algorithms and indicators that reflect each democracy’s electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian uniqueness.

Employing this dataset together with their mathematical equations, Taden and Acheampong were able to count each democracy as a dependent variable and social media penetration as an independent variable. This approach allowed the professors to peer beyond the curtain of these democratic nations and diagnose some of the ramifications of social media.

“I hope this research clarifies how social media can have a positive and transparent impact on democracy,” Taden says. “It allows citizens to hold their leaders accountable by providing them access to information. However, it would be even better if it should prompt the public to leave the social media space and go learn more from reputable outlets.”