Editing Cancer Care: Professor Antonio Gomez and Sophomore Madison Johnson Pursue an Innovative Medical Breakthrough

Is there a cure for cancer?

Since Hippocrates (460–370 BC) gave the disease a name in ancient times, humanity has searched for an answer to this deadly medical dilemma. However, centuries of research, technological advances, and medicinal innovations have not yielded a foolproof remedy. The quest to discover history’s most elusive antidote, at this point, is not unlike hunting a unicorn. Unlikely. Improbable. Impossible.

What if the cure to cancer weren’t a pill or a shot or a magic, digestible elixir available to patients after a diagnosis? What if, in fact, we didn’t have to cure cancer, but we stopped it from developing in the first place?

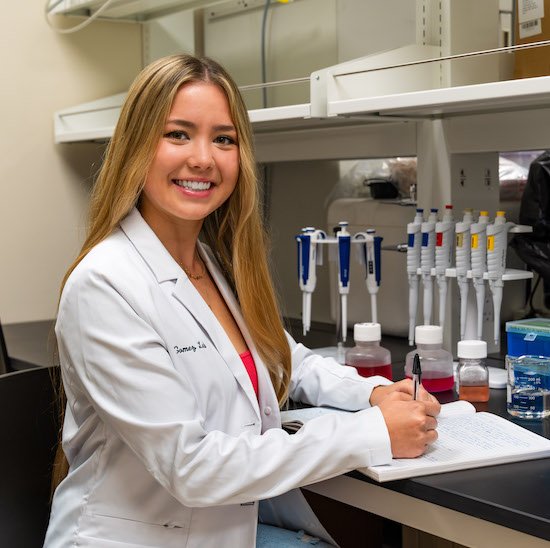

Madison Johnson, a Seaver College sophomore, and Antonio Gomez, an assistant professor of biology, have been asking themselves these questions for the past year as they’ve immersed themselves in the study of preventative cancer care and, possibly, come one step closer to reshaping history.

“Our hypothesis is that there are sleeping, dormant genes in our genome that, when we activate them, can actually cause cancer cells to stop growing,” says Gomez. “This thought has been around for a couple of years, but has remained largely outside of the scientific publications. So our work is a proof of concept.”

Gomez and Johnson’s hypothesis requires the use of CRISPR, a gene-editing tool that allows researchers to target specific segments of DNA for either activation, alteration, or deletion. Though the concept of CRISPR sounds like science fiction, the tool possesses the ability to reshape the reality of the medical landscape. Gomez and Johnson’s hypothesis proves as much, as they believe CRISPR can be deployed to activate specific genes in a strand of DNA that proliferate cancer cell suppressants. The activation of these genes could save those genetically predisposed to cancer.

“I came to Pepperdine wanting to work with CRISPR,” says Johnson. “That was one of my goals for my undergraduate studies. Immediately upon entering the Natural Science Division at Seaver College, I met Dr. Gomez, who was already working with the technology.”

Johnson’s fascination with CRISPR only grew once she started studying the medical possibilities of the technology. Researching alongside Gomez, Johnson learned that CRISPR does more than edit out negative genes; it also possesses the ability to activate positive ones. Hooked, she approached her new mentor seeking an opportunity to study gene editing throughout the summer.

“When she first approached me about further research, I had just completed my first year at Pepperdine, and I didn't have a lab space ready,” says Gomez, with a smile. “ I said, ‘I would love to work with you, but I actually don't have any lab space. I don't even have any equipment or reagents. We're building everything from scratch.’”

A first-generation college student from Arvin, California, Gomez spent his summers as a teen working in local fields. He dreamed of going to college and eventually graduated from the University of California, Berkeley with a degree in chemical biology, prior to earning his PhD in microbiology and immunology at Stanford University. This background accustomed the biology professor to entering unfamiliar territory. Thus, embarking upon relatively unstudied CRISPR concepts was not a difficult step to take.

With little to no lab space or equipment and a dramatically novel concept to explore, Gomez and Johnson launched into their study during the summer of 2023. They poured over the existing literature surrounding their concept, used microscopes, incubators, and CRISPR to implement and observe their experiment, and began recording the first of their findings.

Johnson worked off benches she found in the teaching lab; Gomez continued to construct their own experimental space. The two forged their way forward with the same goal in mind—find a safer solution to treat cancer.

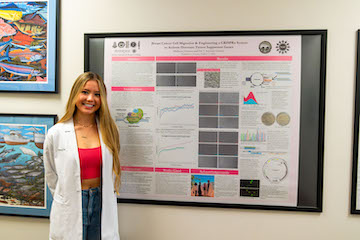

In the midst of the process, they discovered that when one specific gene, GAS1, is upregulated by CRISPR activation, cancer cell growth rates decrease at a dramatic rate. This finding guided the rest of their summer research and experiments.

Racing ahead of an innovation like Johnson and Gomez’s is a conversation about ethics. Much is still unknown about how gene editing could affect human patients and their offspring, but beyond that, there is a larger moral dilemma as researchers, practitioners, and the general public weigh in on the morality of reworking nature.

“There are many different, groundbreaking implications with this technology because it is just so revolutionary,” explains Johnson. “I am just grateful to be learning and researching the topic here at Pepperdine—a Christian institution. It’s a safe place to learn about it. I think it's important to be well educated and conversant about the concept so that, when the time comes, we can provide valuable and ethically informed input.”

Gomez and Johnson considered the murky ethical and moral foundation of CRISPR as they conducted their study. The beauty, they believe, of their potential cancer solution is that rather than altering one’s genetic makeup, it demonstrates that a potential remedy rests within everyone’s DNA already. It simply must be activated.

Gomez explains, “One of the benefits of CRISPR activation technology is that we're not changing the sequences of the DNA itself. We're basically bringing in proteins that will activate a specific gene, but creates no danger of that particular modification being passed on to the next generation. This provides a natural safeguard for patients.”

Today, research regarding CRISPR is ongoing at Pepperdine. After one summer of building lab space and conducting experiments from scratch, Gomez and Johnson are writing a report of their findings that they hope to soon publish in a scholarly journal. In the meantime, Johnson is presented the concept at the Southern California Conference for Undergraduate Research hosted by California State University, Fullerton, on November 18.

While the work is far from finished, Gomez and Johnson’s project is contributing to the worldwide quest to uncover the cure to cancer. Though the battle has been ongoing for centuries, an end could be in sight, and it could help humanity defeat a multitude of troublesome illnesses.

“In the dream scenario, when you walk into the doctor's office, they will have not only a record of your vaccines and blood work, but also an understandable copy of your genome,” says Gomez. “That way we can track, treat, and hopefully cure diseases we may be susceptible to.”